Undomesticated life: A Conversation with Diego Valeriano

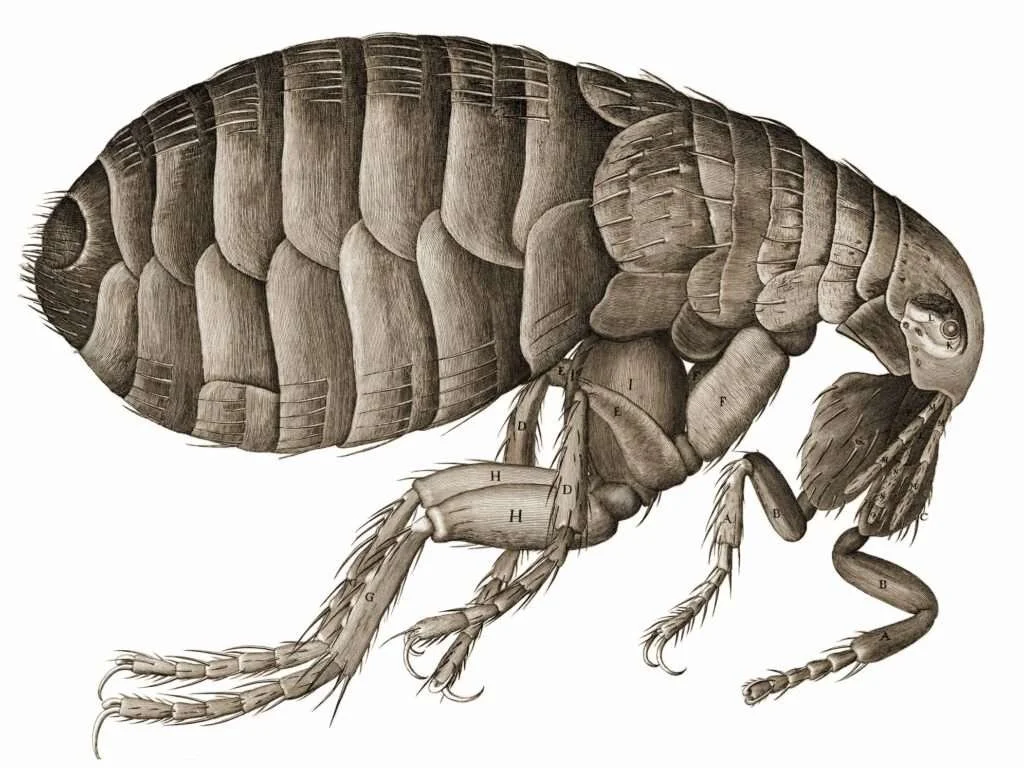

/For Diego Valeriano the end of the world is not a foreseeable event to come, but something that has already taken place in the current ungovernability. Valeriano writes from Buenos Aires, in the outskirts of the Conurbano, where he has worked with street children in villas miserias. He is a sort of anti-pedagogue who claims that he has nothing to teach or to translate into discourse. In the last decade he developed an intuitive mode of writing that describes the daily confrontation of “runfla lives” (a proto-concept that describes everyday people as they traverse the city for daily survival) against the different apparatuses of the metropolis: the police, the social worker, the pedagogue, the psychologist, the professional militant, or the journalist. At the height of Cristina Kirchner’s mandate (2011-2013), Valeriano put forth a controversial thesis that claimed that for large sectors of the population, the new access to consumerism ultimately entailed a sort of “liberation from within”; that is, an intensification of the anthropological texture that rendered the hegemonic fantasy of progressive populism destitute. The turbulence generated by consumption marked a decisive limit to political closure, opening life to other possibilities attuned to the encounters in the territories. The stakes were high, given that the “liberation through consumption” hypothesis stands as an archi-anthropological thesis that dissolves the virtualization of commodified life of the metropolitan order. Valeriano gained a battalion of enemies from both the left and the right. But Valeriano is by no means a philosopher, nor is he a professional writer or even a poet. In the Latin American tradition, the other side of the intellectual lettered city has been traditionally understood as the site of the illiterate subaltern subject. However, this is a formulation that too easily overlooks the fact that both negation and subjectivity are still substitute forms of metaphysics. In Valeriano a clear displacement takes place; mainly, the movement from subaltern subjectivity to the texture of existence. In his speedy descriptions and highly intuitive theses, the matrix of representation is no longer at the forefront; it is rather experience and “segundeo” (which can roughly be translated as “accompaniment”, although it does not really capture the richness of the original Argentine slang that entails a sort of “best-buddy” hang out). Segundeo ultimately refers to the shared clandestine friendship when taking part in something. As an illegitimate successor of Fernand Deligny and Carlo Michelstaedter, we find in Valeriano a passionate defense of an uninterrupted life oriented by desire. Indeed, this intensification emerges and is seen in the youth, as the threshold that escapes the domestication of “ideal types” as well as the norms that govern life. In this sense, Valaeriano’s anti-writing is a love song to the youth as they abandon the faith in the withering of politics. In this interview specifically made for Tillfällighetsskrivande, I talk with Valeriano about his recent book Eduqué a mi hija para una invasión zombie(Red Editorial, 2019), and how the experience of living is already a gesture that undoes our conceptions of politics and subjection.

Gerardo Muñoz

1. Your little book Eduqué a mi hija para una invasión zombie (Red Editorial, 2019) is written with a specific style, a rhythmicity, and completely devoid of concepts. One could say that style is precisely the pace that flees from the justifications, ends, but also the rhetoric of authorial intentions. Style gathers things against every narcissistic pretension of the “I”. In this sense, your writing is also poetic. You have told me before that you would like to write as if you were writing a song. Is this still an important element for you?

When I say that to write is like composing songs, I am referring more to a particular impulse of writing than about a way of actually doing it. To write like a song does not mean that I am actually writing songs. I would not go that far. Rather, it is more like the search for a particular rhythm, a specific velocity, and another temporality. I want to touch what resonates in each body. I also think that the question about “poetics” that you mention is really about how to give form to that which moves you. I want to provide space to the repetition and the lyricism that pounds my head as I walk or go about in the city. What I also like about songs is that they have, aside from an infinite beauty, a confidence in words; that is, an economy of words that opens the infinite possibilities of living those verses. You know, there is nothing more beautiful than songs, because it has something that touches upon how we tell stories. Songs always accompany someone [segundean]. And yes, there is something about anti-writing in songs, but there is also a very beautiful form of writing. So, I want to write as if I were composing a song, but of course I always fail.

2. Let me move from style to tone. There is a strong emphasis in your writing about the relation between an apocalyptic tonality and partying (fiesta). I think that the tonality of our epoch if profoundly apocalyptic. Once an adolescent goes out to the street in Latin American he knows that he might be leaving for the last time. This is a very powerful sentiment or intuition. For years you have talked about how these marginalized lives in late neoliberal consumerism (“vidas runflas”) cope with a fragmented world. Can you tell us a little more about how the apocalypse is lived in the outskirts of the metropolis such as the Conourbano?

I do not think I know well why I say the apocalypse. It seems to me that it is an intuition or a way of saying something. For me it also a code to attune oneself to the present. It is something that takes places, an event. When I say apocalypse it is really another way of saying partying, errancy, death, freedom, holding on to something; but also, an exchange, having certain luck, feeling a discontent, and liberating the drive. The good thing about the apocalypse is that is everything and nothing. It is catastrophic, but also a joke and a possibility. If I were to answer you directly, I would be betraying a mode of writing and those that I love. It is difficult to say how others live (in the Conourbano they live with the means that they find). So, no one truly knows. We can only get a glimpse of the experience here and there, but then we tend to forget it. However, whoever tries to explain how other people should live is immediately a traitor, a translator, or an intellectual. In sum, this person is a vigilante and a liar, because we know that the question of life is an unknown region.

3. Picking up on what you say, let me ask you about “partying” (la fiesta). We have talked about this before: the pandemic has put us under a sort of neo-monastic condition, a new phase of alienation that in a way puts in crisis the possibilities of encounters and gathering of bodies, which is best expressed by the experience of partying. So, the question is simple: what is the future of partying after the virus? Can the party defeat the ongoing process of domestication and reclusion?

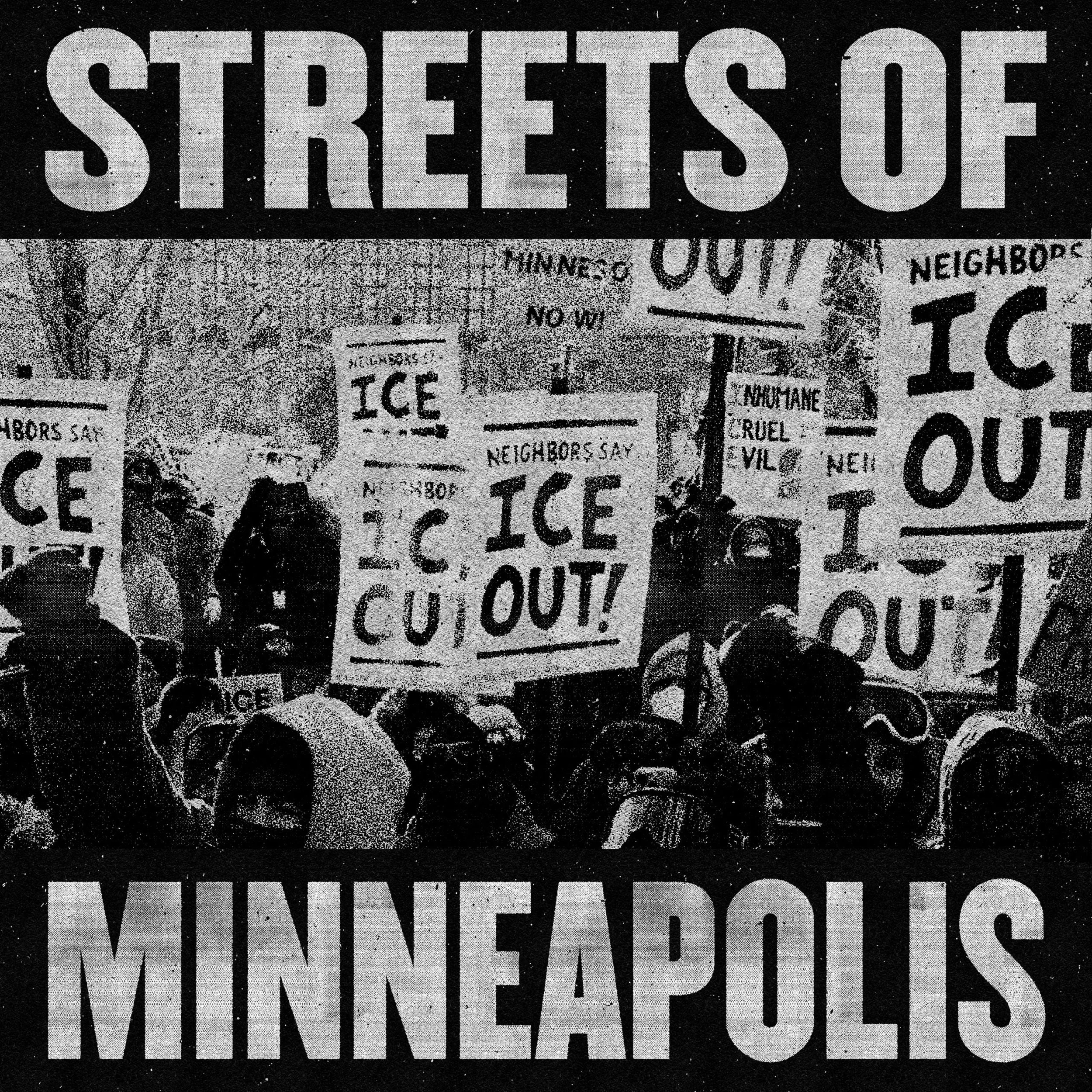

To go back to what we were saying before, I think that partying is the apocalypse. These are two forms of saying more or less the same thing. To party is to dwell, it is a way of producing encounters, but also, at times, of defining struggles. The party is the form of life of the city; in other words, it is the most revealing arrangement of the city (not the metropolis). It is in the party where we become duplicitous (pillos), because partying is always what escapes; what takes place when we take a train or when we become mesmerized at the new things; it is the moment we lose ourselves in acid with our friends; it is going to the football field or taking a stroll in the plaza; it is also the rumors about looting a Chinese market; it is the time of waiting for a local bus and disrespect orders; it is also a way to die on a Friday while resurrecting on a Sunday. This form of partying has always been persecuted. The police cars are always very attentive to the party locations, because when we say “party” it is understood that we mean apocalypse, the youth, vagabond life, delinquency, black market, and hustling. These are all gestures that escape the orders of the state and the market. When I say party, this implies necessarily to be against normal life (“vida ortiba”) and the market, since now bodies are sites of confrontation. Against the neoliberal reduction that identifies the world with life for productivity and extraction; the party, on the contrary, is a form of life that begins by saying “no”.

4. Eduqué a mi hija puts the youth at the center. Of course, the youth seems to be what defies orders, and perhaps this is why it is persecuted, hunted, or disappeared as what recently happened with Facundo Castro. According to Jacques Camatte, the youth is a threat because it proves that there is a life outside the process of domestication. How do you understand the youth in the context of the apocalypse?

The girls and boys are always disrespected, always persecuted, always outside regulatory norms. But the youth is everything that we must defend. If it weren’t for the necessity to control the youth, the practice of the state would be almost nonexistent! The police are always after the youth: they make them disappear, they accost them, and they furiously follow their tracks. But on the other side, the pedagogues, the psychologists, the lawyers, the social workers, the representatives of the local churches, and the leaders of the social movements do more or less the same. Pedagogy here means one thing only: to make them stay put, to ruin their passions, to destroy their language, and to politicize them. An array of futile strategies is articulated with the only end of taming them. The strategy is always the same: let’s silence the voice of discontent so that the pace of the metropolis can continue its march. The girl, the apocalypse, the party, the dwelling, the chaos, the revolution, love, or friendship: when we say these words, we are always talking about the same thing.

5. One last question. A vector that runs through your writing is a separation between politics and life, which some of us have called infrapolitics. It is clear today that politics is on the side of domination and hegemony; where life is a practice of exodus and what escapes the ruined legitimacy of the political. In your terms, what escapes is the anarchic experience of “vidas runflas”. Is this experience slowly abolishing our comprehension of politics, which no longer corresponds to the reality that we are living?

For me the only thing that has any value today is a best-buddy experience (segundeo). What we understand by politics or political form is what develops to counter the friendship of segundeo. Politics is always the expression of you “cannot”, while disciplining, educating, or incarcerating everything that attempts to move away from the aim of making them better producers, more efficient workers, and civilized citizens. This is a way to reformat their habits and codes. So, politics wants to neutralize and organize the discontent, but this is precisely what the runfla form of life upholds. In the end, politics is always about certainties, fixed temporality, location and pedagogy. Luckily, this is everything the runfla life rejects.