Pandemocracy and the State of Exception

/This text on COVID-19, previously published in a shorter version on An und Für Sich, is written by Bruce Rosenstock, Professor at the Departement of Religion at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Professor Rosenstock has written numerous articles and books on ancient philosophy, Jewish thought, and modern theology. In recent years he has engaged deeply with the problem of anthropogenesis and the emergence of life. His book on Oskar Goldberg, Transfinite Life, contextualises the so-called Goldbergkreis in the Weimar period and at the moment he is working on a new book on what he calls Occidental Mythopoetics.

These reflections are not only the product of our current global crisis but also respond to the theoretical challenge of thinking otherwise about the nature of biopolitical governance, the challenge of discovering some resources within the biopolitical to support an insurgent form of life. Recently, Roberto Esposito in Two (2013) has made the attempt to discover in the globalization of sovereign debt the possibility of overcoming the sovereign splitting of the biopolitical decision, between “making live” and “letting die”: “The fact that all states, divided by a clear inequality of resources, are now indebted to an entity as elusive as global finance means that for the first time, perhaps, the world will experience a condition of shared suffering. It is as if splitting had become the general form of unity. We are joined by a debt that separates us even from ourselves, by suspending us from a model of development that produces loss. Since everyone is included in it, we are at the same time also all excluded. The point of arrival for economic-political theology is identity, with no remainders, between inside and outside, whole and part, One and Two.” (Two, 208) Esposito cautions us not to try to return to this condition of this “identity . . . between . . . One and Two” by resurrecting some new form of sovereignty. Instead, he suggests that we create what I am calling a “pandemocracy” out of our globalized condition of being unified by our experience of being split between our identity as owners and our identity as owers. He claims that what “flickers” in our commonality as commonly indebted to one another, our status as Ow(n)ers, is “the law of jubilee,” the law that proclaims an end to debt slavery and restores to each person all the material needs required for living a full life (209). The Jubilee is the opening of a true pandemocracy.

Esposito did not imagine the possibility that it would not be the collapse of the global finance markets that allowed the law of jubilee to flicker, but the global pandemic. Giorgio Agamben correctly identifies the pandemic as the instigation for a sovereign counter-immunity reaction that decides whom to make live and whom to let die. But it is more than that. Even in this sovereign decision, those who are called upon to execute it demonstrate a sacrificial exorbitance that is the sign of those who renounce their ownership of secure life and livelihood in a demonstration of common owership. I am of course referring to the women and men who daily minister to the sick and dying. This is not unique to this pandemic. Thucydides speaks of such self-sacrificing care in his description of the plague that broke out in his besieged city of Athens. In Athens and today, the common owership displayed by the health workers is understood to be grounded in a sacred bond, the Hippocratic Oath. Agamben has taught us about the intimate link between oaths and the sacred. I would suggest that Asklepius, god of healing, is the figuration of the other of sovereign decision between making live and letting die. It is not surprising that Asklepius is himself put to death by Zeus and transformed into a constellation, Ophiuchus, the “snake holder.” The wisdom of the snake is self-regeneration, a.k.a resurrection. It is also what “flickers” on the horizon of our “shared suffering.” The Jubilee is also the promise of a redemption from the bondage of death.

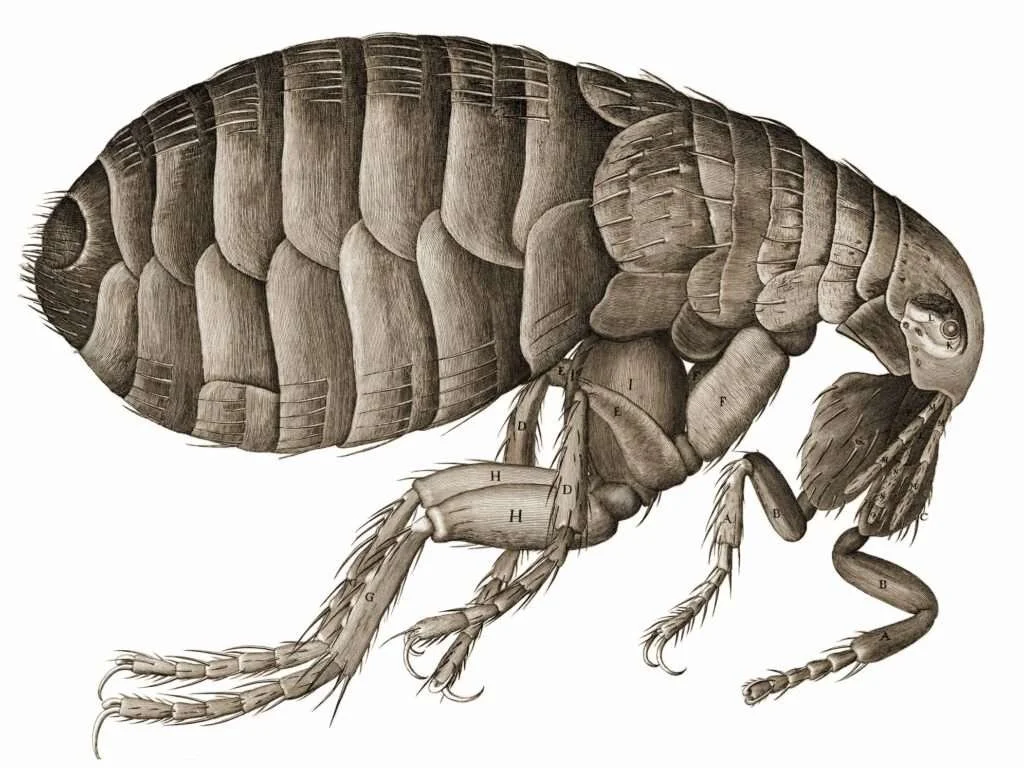

Ophiucus and Serpens constellations from the Mercator celestial globe (Gerard Mercator, 1551 )

Marx, in his 1841 dissertation on Epicurus, had fascinating things to say about constellations, one of them being Ophiuchus. He said that the heavenly bodies (ta meteora) in the ancient world intimated the fulfillment of our species being as one, immortal species, no longer divided between owners of bodies and owned bodies. Each constellation was a unique combination of star-gods. The constellations were the eternal forms of the mythic gods, captured in the instant of their perfect or exemplary activity. Epicurus, whose philosophy of atomism, according to Marx, gave expression to the dissolution of the social bond of ancient polis, could not bear to see the constellations as star-gods. Marx says he could not bear tension between his consciousness of the atomized social condition of his fellow Greeks and the image of an organic unity of immortal star-gods. He could not bear the flickering of another form of life so radically different from his own. He therefore rejected the Greek view of the constellations and argued that they were in fact nothing more than long-lasting but ultimately mortal atomic configurations. Mortal gods. Epicurus thought these mortal gods lived in the “intermundia,” the void between the infinite number of worlds such our own where more stable atomic compounds manage to create planets, a sun, and various life forms. The intermundial gods slowly lose their surface atoms, which preserve the external form of the constellation and enter into the nearest world and then into the dreams of the intelligent beings who dwell within on one or more of the world’s planets (Epicurus had no doubt that intelligent beings existed in other worlds besides ours). Our dreams are full of the effluvia of the intermundial “gods.” They don’t care about us, they merely accidentally shed their skin on us.

Marx thought that Epicurus’s conception of the slowly disintegrating intermundial gods, although it signaled a radical critique of Greek religion, nonetheless failed to offer a concept of divine life that reflected the real species being of humans. Marx of course was a good reader of Feuerbach and knew that any religion worth its salt would offer a close approximation of the true form of the human species being. Skin-shedding atomic gods were nothing more than atomized humans slowly dying alone in their own little worlds. Ironically, it was Greek religion’s concept of the star-gods that more accurately reflected the ideal form of human species being. Each star-god perfectly combined a unique essence with a perfectly matched material substrate (aether), and the immortal life of the star-god captured the ideal human species being, where human activity and the material condition of that activity were in perfect synch with one another. Marx understood that Epicurean atomism was perfectly suited to a culture that had lost its organic unity in the polis and been absorbed into an empire with a distant sovereign. Marx saw that this same condition existed in Hobbes’s day, and he was unsurprised by the return of atomism and Hobbesian materialism. The Hobbesian sovereign, the mortal god, was like one of Epicurus’s intermundial gods, slowly decaying as his “skin” was shed with each new generation. Each atomized member of the sovereign state simply moved about according predetermined laws, the economic laws of capitalist production.

What has become of ta meteora today? What today presents an image of our true human species being, the reconciliation of our species essence and the material conditions of our shared life? In the ancient world, the star-god constellations offered this image according to Marx. I believe that today we see our true species being in the constellation of Asklepius, the snake holder. We are a species that regenerates itself in the work of the healer. Our health workers are the living form of Asklepius. They show us a form of species community beyond the sovereign decision of who to let live and who to make die.

Robert Yelle has recently published a wonderful book, Sovereignty and the Sacred (2019). In a philologically rigorous and historically informed study of the intimate relationship between the myths and rituals associated with sovereign investiture and the sphere of the sacred in general, Yelle demonstrates the doubled and split nature of our political conjunctions, whether in ancient city-states, medieval kingdoms, or modern liberal states. His book should be read alongside Esposito’s Two, tracing political theology (Yelle prefers “spiritual economy”) not only to its Greek and Roman antecedents, but to the Indic precursors of both traditions in Sanskrit myth and ritual. Esposito’s and Yelle’s books are sober accounts of the violence that continually (re)founds our polities and invests sovereignty with the lightning flash of the sacred, the brilliance of the heavens finding a murderous pathway to the earth. Lightning is the violent mediation of heaven and earth, and Zeus is the god who creates a human order that is premised on human mortality and the circulation of death mixed in with every gift (Pandora, the creature he gives to humans, means “all the gifts”, but all Zeus’s gifts are meant to keep humans subject to his mastery.) Yelle and Esposito have not allowed themselves to be blinded by Zeus’s sovereign power, his lightning weapon of death. Like the early Marx, they teach us that the heavens also intimate our common life, a pandemocracy that is no less sacred than the mortal god who demands obedience as the price of our more than “short and brutish” lives. That bargain is revealed today as a sham. We may, as Agamben has suggested, allow ourselves to be duped again by this mortal god’s pretensions. Or we may, as Esposito and Yelle suggest, find another god flickering in the darkness, the god who promulgates the law of jubilee and raises our hope that the snake’s wisdom has not been utterly forgotten.

Bruce Rosenstock